**See below for update**

The

Center for American Progress is a liberal (or progressive, or democrat, or whatever the hell else we’re calling ourselves these days) think tank devoted to:

The Center for American Progress is a nonpartisan research and educational institute dedicated to promoting a strong, just and free America that ensures opportunity for all. We believe Americans are bound together by a common commitment to these values and we aspire to ensure our national policies reflect these values. Our policy and communications efforts are organized around four major objectives:

- Developing a long term vision of a progressive America

- Providing a forum to generate new progressive ideas and policy proposals

- Responding effectively and rapidly to conservative proposals and rhetoric with a thoughtful critique and clear alternatives

- Communicating progressive messages to the American public.

Currently, they are producing a series call

Progressive Priorities that outlines new policy ideas. One of the more interesting ones is called

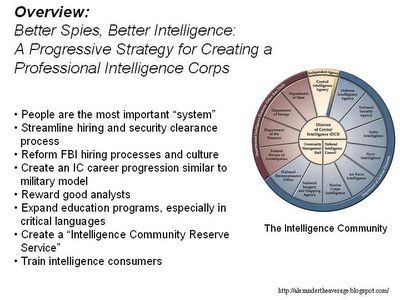

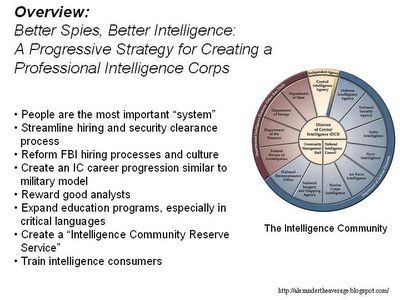

Better Spies, Better Intelligence: A Progressive Strategy for Creating a Professional Intelligence Corps. Regardless of your politics, it’s a good read and there are some noteworthy ideas explored in the paper.

The overall theme of the study is investing in the “human capital” of the intelligence community. Every year, we spend billions on our spy agencies, and our “systems” our second to none. But, that didn’t prevent Sept 11th or the WMD snafu in Iraq. Systems are worthless without the right people to do the analysis. The Center for American progress thinks that we can do better.

Overview Slide (Because a day without powerpoint is like a day without sunshine)

Overview Slide (Because a day without powerpoint is like a day without sunshine)

Here are some areas that I thought were worth exploring:

FBI Culture and Hiring

The obstacles to change at the FBI have been and remain significant. At the time of the attacks, the FBI had critical personnel shortages in nearly every area: agents with counterterrorism experience made up less than 15 percent of its total agent workforce; it lacked any meaningful strategic analytical capability; and it had fewer that 100 specialists in the priority languages of Arabic, Farsi, Pashto, and Urdu. The FBI also remains imbued with a on the Virtual Case File System alone, much of which now appears to have been rendered worthless.The seriousness of the problem raises this issue to the level of presidential action. The FBI also remains imbued with a law-enforcement-first culture that is at odds with the skills and duties central to perform its intelligence function. In interviews withanalysts who were discouraged by the pace of reform, the 9/11 Commission staff found that many analysts were still being significantly underutilized.

more

Although the September 11 attacks provoked a call to service in the country that produced an unprecedented surge in applications to the federal government, real challenges remain in transforming this into more effective Intelligence Community staffing. The FBI received more than 40,000 applications for its special agent vacancies, and 57,000 from aspiring analysts between February and September 2004. According to testimony to Congress by then-Acting CIA Director John McLaughlin, the CIA has experienced a similar surge in applications—totaling between 3,000 and 6,000 per week. A larger applicant pool, however, has not yet led to the Intelligence Community having personnel with the appropriate skills in sufficient numbers.

The FBI’s special agent hiring practices, for example, remain stuck in the past. The qualities the FBI traditionally seeks in special agents—law enforcement experience, legal or accounting backgrounds, and/or military service—are poorly matched to its new mission. Although Director Mueller has asserted that the Bureau is now recruiting with an eye toward intelligence experience—including language specialists, regional experts, computer scientists, and life scientists—FBI special agents still must be hired in one of five entry programs, none of which is intelligence. The Applicant Information Booklet for special agents available on the FBI website was last revised in 1997.

more

The FBI’s analyst and linguist recruitment efforts do not encourage the conclusion that the Bureau has turned the corner towards truly transforming its personnel. The GAO recently reported that through June 2004, the FBI had added only a net of 197 analysts since September 11, 2001, approximately 20 percent of its analyst workforce.

Help Wanted. These guys are hiring.

Why isn't the FBI?

Analysis: This assessment certainly mirrors my own experience with the FBI. When I got demobilized in late 2003, I was looking for a change of pace. My year at CENTCOM has been one of the most intellectually stimulating and challenging of my life, and I wanted to do something like that full time. When I heard that the FBI was hiring lots of new analysts, I was excited. A year of trying to navigate the FBI’s hiring process beat that enthusiasm out of me. (And this blog post will probably finally kill any chance of me getting hired)

The FBI’s hiring process is one of the most convoluted, bureaucratically inept things that I’ve ever seen. Some quick googling shows that I’m not alone in this assessment. I’m not the smartest kid on the block, but I think that I’d be the type of person that the FBI would want. Military Intelligence Background? Check. Real-world intelligence experience in a joint coalition environment? Check. Security clearance? Check. Homeland Security/Emergency Management background? Check. Extensive experience working with all levels of government--state, local, and federal? Check.

Hired by the FBI? Nope. What’s funny is that I can get a job for about any contractor that I want. When I post my resume on monster with my background the Titans, CACIs, and SAICs of the world come calling. But, back in D.C., there is just one little old lady in tennis shoes to sort through all the applications, and clearly she’s overwhelmed. Plus, this is what you get when you go to check for FBI vacancies:

The FBI Intelligence Program continually assesses mission requirements and priorities. This in turn results in program changes. As a result of the most recent program changes, the Intelligence Analyst vacancy announcements from last year that were open from 8/22/2004 through 9/27/2004 have been canceled. No selections will be made from these announcements.

FBI recruitment for Intelligence Analysts reflects these program changes in terms of focus and potential recruitment incentives. The FBI has a new announcement currently open that targets critical skills such as country or language expertise and other similar qualifications. Recruitment bonus offers tie to demonstrated possession of these skills.

We regret any inconvenience caused by the decision to cancel our earlier announcements. Applicants who previously applied to the Intelligence Analyst announcements that opened 8/22/2004 are encouraged to re-apply to the new announcement. New applicants are also welcome.

Read that closely. We’ve just canceled all the applications

from ten months ago. What have we been doing for the last year? I have a couple in that pile so I guess its back to the drawing board. The bad guys are hiring, but we’re canceling applications. Yikes.

Language Training and Education:

The inadequate language skills within the Intelligence Community are particularly troubling because internal analysis from before the September 11 attacks indicated that it lacked depth in this key area. Yet no concerted effort has been made to significantly increase the pool of potential linguists. This failure is reflected in figures from the National Center for Education Statistics that show the United States graduated only 14 students with Bachelor’s, Master’s, or Doctoral degrees in Arabic in 2002, the last year figures are available, representing 0.08 percent of the total degrees obtained in foreign languages that year.

more

Make Education a National Security Imperative

The Hart-Rudman Commission reported in February 2001 that “the capacity of America’s educational system to create a 21st century workforce second to none in the world is a national security issue of the first order. As things stand, this country is forfeiting that capacity.” As we noted earlier, the American education system has not produced sufficient numbers of language or area specialists. The Hart-Rudman Commission highlighted critical shortages in teachers as well. These problems are cumulative, as current shortages spawn more acute shortages in the future.

The David L. Boren National Security Education Act of 1991 created the National Security Education Program (NSEP), which provides scholarships and fellowships to undergraduate and graduate students to study languages, areas studies, and other national security related fields. The Act also provides grants to universities to improve the provision of education in these areas where deficiencies exist. The NSEP is funded by the National Security Education Trust Fund. An $8,000,000 appropriation was authorized for the Trust Fund in the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2005.

The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 established the Intelligence Community Scholarship Program. As a return for each year of assistance, students would commit to a two-year term of service as an employee of an agency in the Intelligence Community. This scholarship program will be under the control of Director of National Intelligence, and while the NSEP is designed to service the broad category of national security, this program is specifically designed to feed agencies in the Intelligence Community.

Analysis: I’ve

commented on this before. Clearly, as a nation we have to do better. As the world learns English, there does not appear to be much of a “market” drive for language skills. You can make money by just speaking (barely in my case) English. But, our intelligence community, military, and diplomatic agencies need to these cultural skills to be effective. Where are the posters of Uncle Sam saying “I WANT YOU…TO LEARN ARABIC”?

Plus who ever heard of these scholarships? Who are we recruiting for this stuff?

Create an Intelligence Community Reserve Service (ICRS)

An effective Intelligence Community is one that can surge to meet the demands of a crisis or imminent threat while maintaining its ability to examine the horizon for emerging challenges. Creating the necessary surge capacity requires the formation of a meaningful Intelligence Community Reserve Service.

Although the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 authorized a National Intelligence Reserve Corps, its implementation is entirely at the discretion of the Director of National Intelligence. The president should instruct the DNI to work with Congress to establish a robust Intelligence Community Reserve Service. Such a service would enable the Community to retain a capability in critical areas when employees retire or resign. Furthermore, it would provide a dedicated reserve similar to the military’s where individuals are recruited and trained specifically for the reserve force.

This dedicated reserve component could be fed by a program similar to the military’s Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), in which potential reservists receive stipends in exchange for periods of training and active duty. Reservists would be required to maintain security clearances and receive regular training to ensure that their skills are current. A reserve corps would also enable the Intelligence Community to draw on the expertise of people outside of government service.

Analysis: This is the most intriguing and perhaps least workable proposal. Effectively, we have an ICRS. They’re called

contractors. CACI, SAIC, Titan, DynCorp, and everybody else have their fingers in the pie. However, I’m not sure if this is always the best use of our money. (oops there goes more hiring opportunities)

One of the things that I’ve noticed in the reserves is that how many reserve intelligence soldiers are contractors. This year, I’ve had several of my guys get sent to Iraq not as soldiers, but as civilians. So, I’m stuck with soldiers on my roster who aren’t available, and the competing requirements aren’t always well-balanced.

There will probably always be a place for contractors in modern war, but the creation of a ICRS would build in additional surge capacity like we have with our military reserves. It would also allow us to tap into unexploited resources within our society. There are plenty of folks out there who have viable skills, but for whom there is not a full-time need. Many people have no interest in being a full-time spook or soldier, but would be willing to help out their countries in a crisis.

Academia is a great place to look for brain-power.

Not every intelligence mission requires somebody to carry an M-4 or be a graduate of the “farm”.

Document Exploitation is a great example of an intel discipline where an academic might excel. Essentially a clearance and some specialized training is all that separates reserve intelligence soldiers from regular citizens. A clearance, training, and highly specialized knowledge that takes years to develop might just make the idea of a ICRS worth exploring. Hell, I'd join...unless the FBI was managing the hiring process.

Training for Intelligence Consumers

The government invests significant resources to determine whether an official can be trusted to receive classified intelligence information, yet it devotes almost no energy to ensure that the official has the skills necessary to interpret that information properly. The NSC should oversee a program that requires all intelligence consumers to undergo training on how to interpret and evaluate material received from the Intelligence Community. For example, new employees in the Executive Office of the President should meet a series of requirements when first taking their positions. Training in the proper use of intelligence should be one of those requirements.

Analysis: “Blame the S-2,” is a common refrain in the Army. Its always “bad intelligence” but never bad decision making that leads to failure. I’ve found that the best military commanders are the savviest consumers of intelligence.

My boss on the CJTF-180 LNO team at CENTCOM was a ruff and tuff, Airborne-all-the-way field artillery officer. But, he understood intel. Hell, he loved it and knew just as much about it as I did. Later he was assigned to be a Brigade Fire Support Officer in Iraq, and there is no doubt in my mind that he made great decisions because of his ability to consume intelligence information and understand what it can and can’t do for you.

Building a program that makes government officials and politicians better consumers of intel would be a step in the right direction. A good model is what the

Texas Division of Emergency Management requires of its elected officials. If you are an elected official in Texas and your jurisdiction receives any kind of emergency management grant funding you must take this course:

Principles of Emergency Management (G230) * Hours: 16

Description: This course consists of four modules. The first module includes the concepts of emergency management and its integration of systems, basic definitions, identification of hazards and their analyses. The second module outlines the role of the local emergency manager. The third module addresses the coordination of various systems and agreements among various governments. In the fourth module, the participants demonstrate their abilities to work and apply the skills and information gained in the first three modules.

Target Audience: Elected officials, local and state emergency management personnel, senior staff of departments charged with emergency responsibilities, members of volunteer groups active in disasters.

No class, no money. Imagine if every new congressman had to take an “Intelligence 101” orientation before they could be sworn in.

Final Analysis: The ideas in this paper are worth exploring, and some of them are pretty damn good. Of course, labeling these ideas as “progressive” (read not Republican) is not good enough to change anyone’s vote.

In the Army you use the military decision making process when you are preparing for an operation. In this process you develop at least two seperate courses of action to compare and wargame before producing your final plan and operations order. If a potential course of action is to be included in the further mission analysis it must meet the criteria of being “suitable, feasible, acceptable, and distinguishable" from other courses of action.

All the ideas advanced in this paper meet the first three criteria. They are set of workable solutions to some tough problems. However, they are not truly “distinguishable” as a refection of any sort of “progressive” ideals. I believe that most intelligence and security problems are (or should be) politically neutral. Both sides agree we need a strong defense and smart spies. But, a conservative think tank could have come up with these ideas just as easily as a liberal one.

What it all boils down to is leadership. You show me a candidate who makes ideas like this a part of his platform, and then I’ll show you somebody who might get my vote-- Democrat or otherwise.

Update: Praktike over at

Liberals Against Terrorism links

links to this post with the headline "The FBI is a Joke". Having worked with/around the FBI, I respectfully disagree. The FBI is a world-class organization filled with some great, highly skilled people. The capability that they bring to the fight is second to none.

However, this doesn't mean that the FBI doesn't have some big faults. All large organizations do. Personally, I'll probably re-apply for an analyst position once they are posted again. (Although my chances are probably blown now...) I've been part of two world-class organizations--101st ABN (ASSLT) and CENTCOM--and there is nothing more satisfying than being on a team like that.

The FBI is better than its hiring practices would suggest. That's all I wanted to point out. But, thanks for the traffic Praktike. I hope all the newcomers are enjoying my stuff.