Your Homeland Security Tax Dollars at Work

Now this is an interesting use of your tax dollars.

LOS ALAMOS, N.M.-- Deep inside the cave-like laboratories of the legendary research center that created the atomic bomb, scientists have begun work on a Manhattan Project of a different sort.

In the wake of Sept. 11, 2001, they have been constructing the most elaborate computer models of the United States ever attempted. There are virtual cities inhabited by millions of virtual individuals who go to work, shopping centers, soccer games and anywhere else their real life counterparts go. And there are virtual power grids, oil and gas lines, water pipelines, airplane and train systems, even a virtual Internet.

The scientists build them. And then they destroy them.

***

"We're trying to be the best terrorists we can be," said James P. Smith, who is working on simulations of a smallpox virus released in Portland, Ore. "Sometimes we finish and we're like, 'We're glad we're not terrorists.'

But, some disagree on the value of this program:

Some urban planners have criticized the project for its cost -- each simulation can cost tens of millions of dollars -- and have argued that such modeling can never be precise. A book on public health threats by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, for example, notes that some critics say simulations "cannot provide clear evidence for or against any option." Advocates say the exercise is providing crucial information for protecting the country.

Analysis: The most powerful simulation in the world is not going to be able to account for human behavior. But, I see value in this program especially when I read this:

In one simulation, Smith unleashed the smallpox virus in a university building in downtown Portland, with several students becoming victims. Soon after the 10-day incubation period passed, hospitals throughout Portland began to report cases. Smith's computer chronicled the devastation. Day 1: 1,281 infected, zero dead. Day 35: 23,919 infected, 551 dead. Day 70: 380,582 infected, 12,499 dead.

The toughest variable in disaster planning is people and their behaviors, and a simulation that gives planners more insight into behavior is valuable. One of the artificialities in emergency exercises is always the human factor. It’s hard to “script” things like the Portland smallpox simulation.

Now, I do have one problem with this program. I’m in this business and I never heard of these simulations until I read about it in the Washington Post. Apparently they are classified. But, if they are so secret that responders can’t get access to the information, they are useless. Who is going to respond to a smallpox outbreak in Texas? Not the 100 pound brains in Los Alamos.

This illustrates a deeper problem in our homeland security efforts. Many federal programs are classified to the point that non-federal responders can’t get access to the info. Or if they do, it’s so watered down to the point of uselessness. Clearly some of this information needs to be classified, but we haven’t developed many solutions to getting it into the hands of the right people.

Of course no amount of simulation and planning can save us from this stupidity:

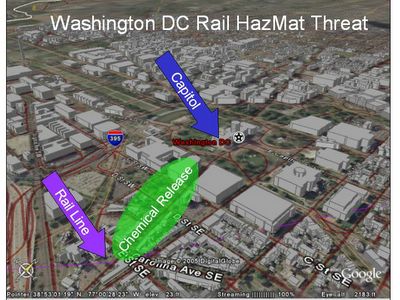

The HazMat threat.

The weakest point in America's defense against terrorism may be an inconspicuous little bridge a few blocks from the Capitol. Rail tanker cars filled with deadly chemicals pass over the bridge, at Second Street and E Street SW, on their journeys up and down the East Coast. The bridge is highly vulnerable to an explosion from below, and if deadly chemicals were released on it, they would endanger every member of Congress and as many as 250,000 other federal employees.

***

When antiterrorism experts try to predict what could happen in the next 9/11 attack, the dispersal of deadly chemicals is at or near the top of their list. An assault on a chemical plant or a rail car filled with chemicals would turn another unremarkable part of the infrastructure into a powerful instrument of death. An attack on a single rail tanker filled with chlorine could kill or seriously harm 100,000 people in less than an hour. Because of its location in the middle of official Washington, a chlorine leak from a rail tanker on the bridge at Second Street could endanger much of the federal government, including Congress and the Supreme Court.

***

Earlier this year, the City Council in Washington passed a law prohibiting the transport of ultrahazardous materials within 2.2 miles of the Capitol. But CSX, the railroad that operates the two main lines running through the district, has gone to court to challenge the law, which would add to its costs. It claims that city governments do not have the power to interfere with interstate rail shipping. A federal court has blocked the law from taking effect, though CSX has temporarily stopped shipping ultrahazardous materials on the rail line closest to the Capitol.

The Bush administration filed a brief supporting CSX in its challenge to Washington's law, and, incredibly, it has made no effort to do the job with federal regulation. When it comes to defending the nation from terrorism, the president and the Republican leadership in Congress have been unwilling to make large corporations, many of them big campaign donors, shoulder their share of the burden. Washington's residents and employees should not have to risk their lives to save CSX the cost of rerouting shipments of ultrahazardous materials.

Analysis: The quoted casualty figures from the chlorine leak in a railcar sounds a little alarmist to me. A lot of things would have to go “right” in order to produce that much devastation from a single rail car. But, make no mistake; there is some BAD stuff out there on the rails. Cities should absolutely have the right to establish hazardous materials routes that restrict the most dangerous cargo from transiting through densely populated areas. Even without terrorism, there are still plenty of transportation accidents that cause spills.

So the bottom line is that we’re spending millions of dollars a year running cool simulations that are so classified that no one can see them. And our nation’s capitol is may continue to be under threat from hazardous materials because re-routing them is bad for business. Like I said, the toughest variable in emergency planning is human behavior.

2 Comments:

I agree with you that the human behavior part is always the toughest thing to "model" - it's always been the weak link in chem-bio defense modeling as well. Will the troops be poorly trained or well trained? How many will get their masks on in time? How do you model the degradation of wearing MOPP gear? etc etc.

It seems like the modeling of plumes and hazards is the relatively easy part, but of course that's all guesses also, dependent upon weather, skill of the operator, particular chemical composition, etc etc. I've always felt (and others I thnk) that the smallpox predictions are way overblown, grossly exaggerating the contagiousness of the agent. I think they must assume no treatments are taking place and no one is noticing the coughing, scab-encrusted individuals among them.

But re: the DC trains, that's more complicated. Again, the chlorine plume casualties are exaggerated, assuming no one shelters in place, no one leaves the area when they see a yellow mist coming in, no one evacuates, we're all standing there like dummies. The weather's perfect, and instead of a hot day like today which would take all the CL2 gas straight up in the air, it all lies down on the ground. Too many worst-case scenarios for me.

But most important is not the predictions, but the risk management aspects. First there is that pesky thing about federal laws - you know, no state can mandate laws on interstate traffic. Second, the best maintained rail lines are the ones that go through major cities - so do you really want to risk MORE lives by using less-well maintained rails that travel further and expose potentially more people? Third, is the plume expectations really realistic? I keep referencing the 2001 Baltimore HAZMAT incident where a tanker car full of hydrochloric acid burned (along with a few other tankers) and no one evacuated, no one stopped the double header in Camden yards, etc etc. So I think these studies don't help - they hinder with this sensationalistic "what if" stuff - unless you risk managers apply common sense.

Smallpox is bad because it is a contagious disease. And vaccine stocks are very limited. Whether its a practical terrorist weapon -- how would they get it? -- the long struggle which eliminated smallpox does make it a well-understood bioweapon which can be simulated.

For what can go wrong, look at the outbreak of Foot and Mouth disease in Britain, in 2001. There's a lot of knowledge about the disease and how it spreads. The official response in the UK seems to have been flawed; weakened by a lack of planning, and a lack of testing of plans.

It's well-documented on the net, and was very thoroughly discussed in the uk.business.agriculture newsgroup at the time.

It's a strong argument for the sort of simulation being done, and also for the results to be applied; for the results to get to the people who will have to sort out a real attack.

As for chemical cargoes, don't forget road tankers. Here in the UK, at least, a small country, there aren't the long-distance movements of large consignments that justify rail freight.

In principle, it wouldn't be hard to gridlock LA.

Post a Comment

<< Home